Hidden Gems Behind the AI-Data Center Boom

Hidden Gems Behind the AI-Data Center Boom

What’s AI? It’s Data

Well-known is the relation between AI and data centers. AI tools send requests over the internet to a giant building full of computers called a data center, in which the models analyze massive amounts of data, often using specialized Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) for parallel processing housed on data center racks. The rise of AI has in tandem field demand for the processors, memory, storage and electricity inside these centers. Between 2023 and 2030, the amount of AI-ready data center space is expected to grow by about 33% every year, and about 40% of that growth will come from generative AI (tools like ChatGPT).

Most of this new AI computing happens inside public cloud data centers, which are giant buildings full of computers, owned by big tech companies like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure and IBM Cloud. They let millions of people and businesses use shared computing power instead of having to own their own servers.

The biggest of these centers, at millions of square feet and holding tens of thousands of servers, and hyperscalers. By 2030, as much as 65% of AI work in the US and Europe could be happening inside these giant hyperscale data centers.

But there’s a catch: data centers can’t grow just because companies want more AI. They are real physical systems requiring and bound by land, electricity, cooling and government approval. These areas receive less attention, and thus hold hidden trends underlying the AI-data center boom: trends which warrant the attention of retail investors.

More Like Housing than Tech

Although data centers are associated with tech, they fundamentally meet the definition of real estate assets. They are physical buildings that sit on limited land, and its value comes from where it is located, whether it has access to power and cooling and how long companies agree to rent space inside it.

The scale of this market is already substantial and growing rapidly. Globally, there are close to 900 hyperscale data centers, a number which could double over time, with hyperscale facilities potentially accounting for around half of global data center capacity as AI and cloud workloads continue to expand.

The rapid shift toward hyperscale centers has also changed how ownership works. In the past, many big tech companies built and owned their own data centers. Now, however, most prefer to lease space rather than own it themselves. The mix has moved from roughly a 50-50 balance to closer to 70-30, with companies such as Amazon, Google, and Meta choosing long-term leases instead of buying land and constructing buildings. These leases often last 15 years or more, which means whoever owns the building — often a third-party landlord — receives reliable long-term income.

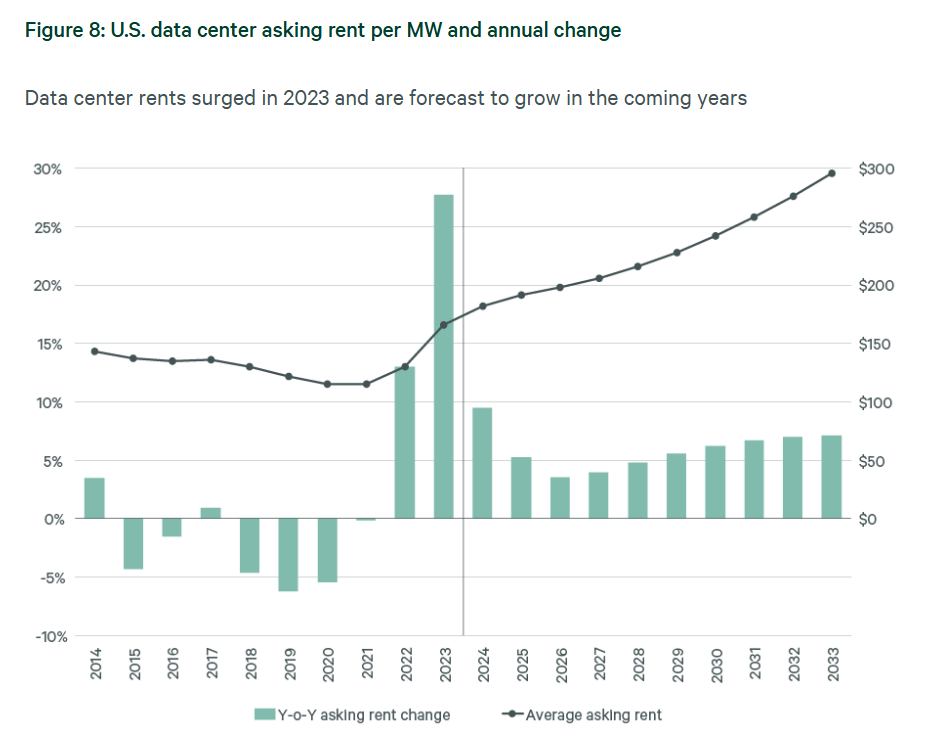

The combination of long leases and more companies choosing to rent has created a situation where demand is extremely high, but available space is almost nonexistent. Vacancy rates in key markets are near historic lows. In Northern Virginia, which is the world’s largest and most important hub for data centers, vacancy rates are below one percent — meaning almost everything is already filled. Because there is so little space available and so much demand, rents have surged in recent years, reversing nearly a decade of flat or declining rents for US data centers.

As a result, this environment has been particularly favorable for data center real estate investment trusts (REITs), which are companies that specialize in owning and leasing data center facilities.

More Power!!

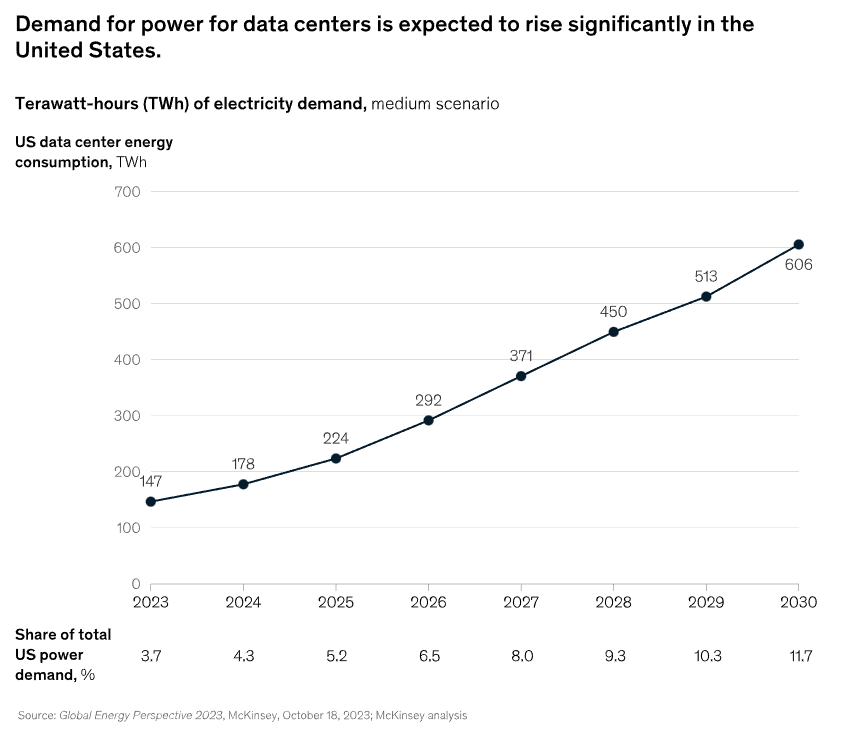

If data centers are the physical backbone of the digital economy, electricity is the binding constraint that determines how fast that backbone can grow. Generative AI has the potential to create between $2.6 trillion and $4.4 trillion in economic value around the world. But to even reach a quarter of that value by the end of the decade, the United States alone would need 50 to 60 gigawatts of additional power, roughly the amount of electricity used by millions of homes, for data centers. Part of the reason this demand is rising so fast is because new AI chips, like NVIDIA’s latest processors, use as much as 300 percent more power than earlier models.

The size and energy needs of data centers have already grown at a dramatic pace. 10 years ago, a data center that used 30 megawatts of power was considered huge. Today, hyperscale campuses using around 200 megawatts are normal, driven by AI workloads that require far more computing power and therefore far more electricity beyond traditional cloud computing. AI-ready data centers also use energy much more intensely because they pack large numbers of extremely powerful servers into tight spaces. The amount of electricity drawn by servers per rack (a tall metal frame that holds stacked servers) — called power density — has already doubled in just the past two years and is expected to almost quadruple to about 176 kilowatts per square foot by 2027. As more power is concentrated in smaller areas, local electrical systems face greater stress. By the end of the decade, global data center electricity demand could rise by as much as 165 percent compared with 2023.

Importantly, the biggest problem is not necessarily that the world cannot produce enough electricity but rather the ability to deliver it. In many places, the power grid — the system of wires, substations, and transmission lines that delivers electricity — is not built to handle such enormous new loads. Even in regions where enough electricity technically exists, connecting a new data center to the grid can take years because the infrastructure is not ready. Fixing this will require massive investment. Analysts estimate that about $720 billion in spending on the electrical grid will be needed by 2030 to support rising power demand, and data centers will be a major reason for that investment.

This dynamic places utilities and grid infrastructure at the center of the data center investment story. Companies supporting the expansion and modernization of the power grid are now one of the chief enablers of future growth.

Take a Chill Pill

As modern AI chips use far more electricity than older ones, and almost all of that electricity turns into heat. Problematically, any older data centers — which mainly relied on blowing cold air across servers — are starting to reach their heat limits. This has triggered a sharp rise in demand for advanced cooling and thermal infrastructure. The global data center cooling market, valued at approximately $14.2 billion in 2024, is projected to grow to over $34 billion by 2033, growing by roughly 10 percent every year.

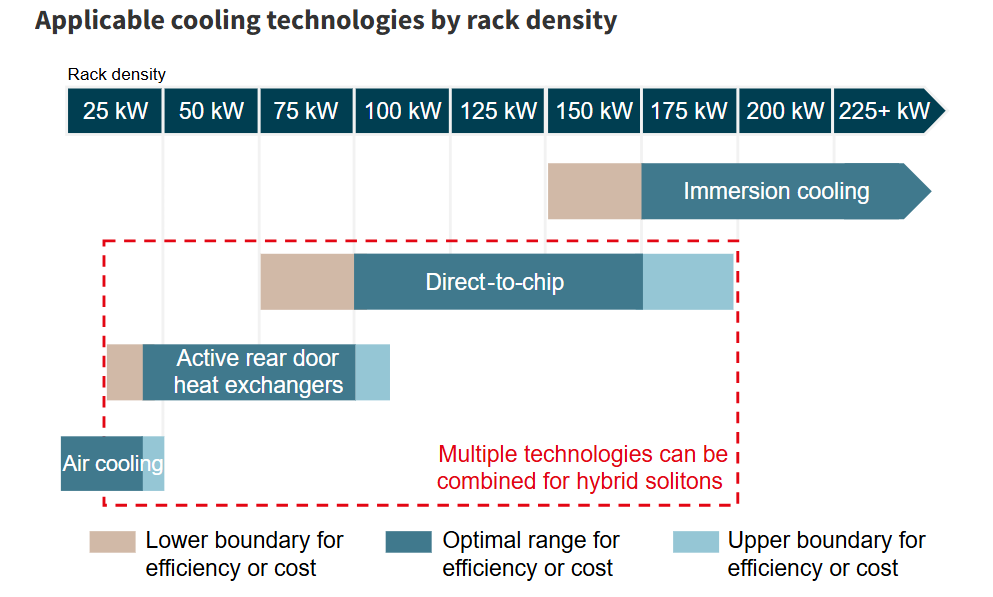

This growth reflects a larger shift in how data centers are built. In hyperscale facilities, the amount of electricity used by each rack now often reaches 20 to 30 kilowatts per rack, and some AI-focused setups already exceed 100 kilowatts. Once cooling requirements reach that level, simply blowing cold air is no longer practical or affordable. There are limits to how much air can physically flow through a building, how floor layouts can be arranged and how much energy would be required to cool everything. Because of these constraints, operators are being forced to adopt more advanced, targeted cooling options.

Many new data centers now use hybrid cooling approaches, typically consisting of about 70 percent liquid cooling and 30 percent air cooling. Liquid cooling means circulating a coolant — often water or a special liquid — close to or directly around the hottest components. One popular design is called a rear-door heat exchanger, which removes heat from the back of the rack right as it leaves the servers. An even more direct technology, known as direct-to-chip cooling, sends liquid through tiny tubes that run very close to the chip itself, pulling heat away almost instantly.

The rapid shift toward liquid and hybrid cooling architectures creates opportunities across a relatively underappreciated segment of the data center value chain.

What to Consider

In alignment with these trends, you may consider:

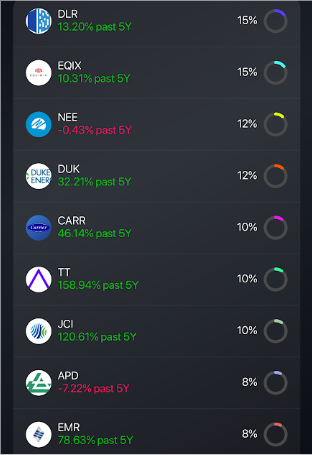

- Companies owning, operating, or leasing hyperscale-ready space to cloud, AI, and enterprise tenants:

- Digital Realty Trust (DLR)

- Equinix (EQIX)

- Utilities and power providers enabling massive electricity demand

- NextEra Energy (NEE)

- Duke Energy (DUK)

- Companies supplying precision cooling, airflow, heat exchangers and building-system control for high-density racks

- Carrier Global (CARR)

- Trane Technologies (T)

- Johnson Controls (JCI)

- Emerson Electric (EMR)

- Air Products (APD)

And you can get invested in these through a custom portfolio created by Bloom: